Biggest ever Leonardo da Vinci exhibition to open in Paris

Louvre will host works of Italian artist after long-running political spats and legal battles

Angelique Chrisafis in Paris

Published on Sat 19 Oct 2019 05.00 BST

The most important blockbuster art show in Paris for half a century

took 10 years to prepare and was nearly thwarted by the worst diplomatic

standoff between Italy and France since the second world war. With days

to go before the opening, there is still no sign of whether one of the major works will appear.

The Louvre’s vast Leonardo da Vinci exhibition

to mark 500 years since the death of the Italian Renaissance master

will finally open next week as the world’s most-visited museum prepares

to handle a huge influx of visitors.

One of the

most expensive exhibitions ever staged in France, it is the first time

that such a large number of Leonardo’s drawings, sketches, writings and

paintings have ever been brought together.

But a question mark still hangs over whether Salvator Mundi

— the world’s most expensive painting — will be loaned. Mystery

surrounds who owns the painting, a depiction of Jesus in Renaissance

dress, which was once thought to be held in the Gulf. Unusually, the

exhibition space has been designed to accommodate pictures arriving or

being refused at the last minute. “We’ve never been in this situation

before,” a museum representative said.

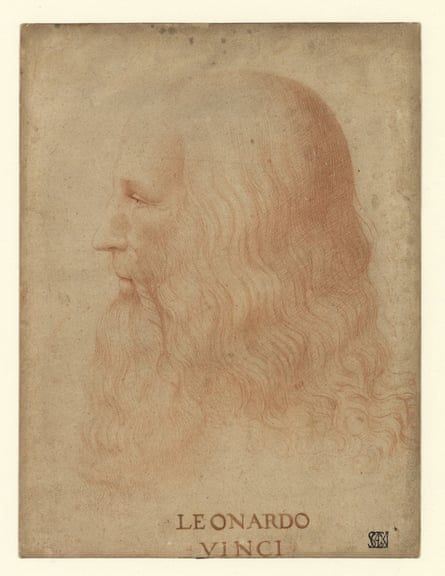

Leonardo,

whose life has been a constant source of myth-making, is considered a

visionary genius – a painter, scientist, engineer and inventor. Born the

illegitimate son of a notary in the Tuscan hill town of Vinci in 1452,

the Italian humanist worked in Florence and Milan,

and spent his final years at the court of the French king Francis I in

the Loire, where he died on 2 May 1519. Since then what is known on his

life has been pored over and seized upon; his vegetarianism and interest

in animal welfare have been cited by French anti-hunting groups while

the androgynous faces in many of his portraits are considered by some as

a modern questioning of gender.

At

the heart of the Louvre’s exhibition are the lessons that can be

learned about Leonardo’s personality from the awe-inspiring realism in

his work: portraits such as La Belle Ferronnière, the Mona Lisa or his

depiction of Saint John the Baptist.

Leonardo

painted relatively little – there are only about 15 remaining paintings –

of which nine are in this show. He worked painstakingly slowly, often

spending more than a decade on a painting. The exhibition includes many

of his outstanding drawings. The curators argue that his interest in

science – particularly astronomy, botany and his constant grappling with

mathematical problems – was not a digression that pulled him away from

art, but was central to his quest to achieve perfection in his painting.

“He

had an ability not just to depict things from the outside, but to also

show what was inside: the movement and vibration of life, the inner

emotions,” said Louis Frank, one of the show’s curators.

Yet the Mona Lisa

– one of the main attractions for the Louvre’s 30,000 visitors a day –

will remain upstairs in its usual permanent hanging place. The temporary

exhibition space devoted to the Leonardo show can only accommodate

7,000 people per day and the museum did not want to prevent other

visitors seeing it. There will also be a virtual reality experience of

the Mona Lisa for the first time. As the Louvre faces ever higher

visitor numbers, the Leonardo exhibition will only be open to people who

have pre-booked.

The whole exhibition was in danger last year when Leonardo was dragged into a long-running political spat

between Italy’s then far-right ruling League party and France’s

president, Emmanuel Macron. Italy said it would cancel the loan of some

paintings, accusing France of trying to take centre stage in the

commemorations marking 500 years since the painter’s death. “Leonardo is

Italian; he only died in France,” one far-right MP said.

The row was finally resolved but then a last-minute legal challenge this month nearly stopped da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man –

a study in anatomical proportions – from appearing. An Italian heritage

group said the drawing, which is kept in a climate-controlled vault at

the Accademia Gallery of Venice, was too fragile to travel

and risked being damaged by lighting in the Louvre if displayed for a

long period. A court ruled the work could travel. It is currently in

transit, and will arrive next week to be shown for a limited period.

Vincent

Delieuvin, one of the show’s curators, said the exhibition would

explain how Leonardo established that the secret to creating perfect

paintings that laid bare human nature was to capture light, shade and

movement. For Leonardo, it was about opening one’s mind to “an absolute

No comments:

Post a Comment